Международный эндокринологический журнал Том 14, №7, 2018

Вернуться к номеру

Вплив додаткового призначення вітаміну D на інсулінорезистентність та жорсткість артерій у хворих на гіпотиреоз

Авторы: Pankiv I.V.

State Higher Education Institution of Ukraine “Bukovinian State Medical University”, Chernivtsi, Ukraine

Рубрики: Эндокринология

Разделы: Клинические исследования

Версия для печати

Актуальність. У нещодавніх епідеміологічних дослідженнях виявлено вірогідні зворотні взаємозв’язки між рівнями вітаміну D, інсулінорезистентністю (ІР) і серцево-судинними захворюваннями. Однак лише в декількох інтервенційних дослідженнях було проведено оцінку впливу додаткового призначення вітаміну D на серцево-судинний ризик, жорсткість артерій у хворих на гіпотиреоз. Мета дослідження — визначити вплив додаткового призначення вітаміну D на серцево-судинний ризик у хворих на гіпотиреоз, у тому числі метаболічні параметри, ІР і жорсткість артерій. Матеріали та методи. Під спостереженням перебувало 55 хворих на гіпотиреоз, які отримували замісну терапію левотироксином. З дослідження виключили пацієнтiв, які отримували препарати вітаміну D або кальцію. Учасники дослідження були розподілені в групу, якій було призначено вітамін D (холекальциферол у дозі 4000 МО в день; n = 30), і контрольну групу (отримувала лише левотироксин; n = 25). Проведено порівняння показників ІР (оцінка моделі гомеостазу (HOMA-IR), кісточково-плечового індексу) до і після спостереження впродовж 12 тижнів. Результати. Характеристики хворих двох груп на початку дослідження вірогідно не відрізнялися. П’ятдесят п’ять учасників завершили дослідження згідно з протоколом. Наприкінці спостереження показники 25-гідроксивітаміну (25(ОН)D) були вірогідно вищими в групі, що отримувала вітамін D, аніж у контрольній групі (32,7 ± 7,2 нг/мл проти 17,1 ± 6,3 нг/мл, p < 0,05). У той же час не встановлено відмінностей за показниками індексу HOMA-IR і змін жорсткості артерій між групами хворих. Висновки. Додаткове призначення вітаміну D впродовж 12 тижнів ефективно підвищує вміст 25(ОН)D в крові. Однак впливу такого лікування на показники серцево-судинного ризику (ІР та жорсткість артерій) у хворих на гіпотиреоз не встановлено.

Актуальность. В недавних эпидемиологических исследованиях выявлены достоверные обратные взаимосвязи между уровнями витамина D, инсулинорезистентностью (ИР) и сердечно-сосудистыми заболеваниями. Однако лишь в нескольких интервенционных исследованиях была проведена оценка влияния дополнительного назначения витамина D на сердечно-сосудистый риск, жесткость артерий у больных гипотиреозом. Цель исследования — определить влияние дополнительного назначения витамина D на сердечно-сосудистый риск у больных гипотиреозом, в том числе метаболические параметры, ИР и жесткость артерий. Материалы и методы. Под наблюдением находилось 55 больных гипотиреозом, которые получали заместительную терапию левотироксином. Из исследования исключены пациенты, получающие препараты витамина D или кальция. Участники исследования были распределены в группу, которой был назначен витамин D (холекальциферол в дозе 4000 МЕ в день; n = 30), и контрольную группу (получала лишь левотироксин; n = 25). Проведено сравнение показателей ИР (модель гомеостаза (HOMA-IR), лодыжечно-плечевого индекса) до и после наблюдения в течение 12 недель. Результаты. Характеристики больных двух групп на начало исследования достоверно не отличались. Пятьдесят пять участников завершили исследование согласно протоколу. В конце наблюдения показатели 25-гидроксивитамина (25(ОН)D) были достоверно выше в группе, получавшей витамин D, чем в контрольной группе (32,7 ± 7,2 нг/мл против 17,1 ± 6,3 нг/мл, p < 0,05). В то же время не установлено отличий по показателям индекса HOMA-IR и изменений жесткости артерий между группами больных. Выводы. Дополнительное назначение витамина D в течение 12 недель эффективно повышает концентрацию 25(ОН)D в крови. Однако влияния такого лечения на показатели сердечно-сосудистого риска (ИР и жесткость артерий) у больных гипотиреозом не установлено.

Background. Recent epidemiological studies revealed a significant inverse relationship between vitamin D levels, insulin resistance (IR), and cardiovascular diseases. However, few interventional studies have evaluated the effect of vitamin D supplementation on cardiovascular risk, such as IR and arterial stiffness in hypothyroidism. The purpose of the study is to investigate the role of vitamin D supplementation on cardiovascular risk in patients with hypothyroidism, including metabolic parameters, IR, and arterial stiffness. Materials and methods. We enrolled 55 patients with hypothyroidism who were taking levothyroxine medications. We excluded patients who were taking vitamin D or calcium supplements. Participants were randomized into the vitamin D group (cholecalciferol 4,000 IU/day, n = 30) or the control group (only levothyroxine, n = 25). We compared their IR (homeostatic model assessment (HOMA-IR)) and arterial stiffness (brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity) before and after 12 weeks of intervention. Results. The baseline characteristics of the two groups were similar. A total of 55 participants completed the study protocol. At the end of the study period, 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) levels were significantly higher in the vitamin D group than in the control group (32.7 ± 7.2 ng/ml vs. 17.1 ± 6.3 ng/ml, p < 0.05). There was no difference in HOMA-IR or changes in arterial stiffness between the groups. Conclusions. Our data suggest that vitamin D supplementation might be effective in terms of elevating 25(OH)D levels. However, we identified no beneficial effects on cardiovascular risk in hypothyroidism, including IR and arterial stiffness.

гіпотиреоз; інсулінорезистентність; дефіцит вітаміну D; жорсткість артерій

гипотиреоз; инсулинорезистентность; дефицит витамина D; жесткость артерий

hypothyroidism; insulin resistance; vitamin D deficiency; vascular stiffness

Introduction

Vitamin D function as a hormone is to regulate bone metabolism via calcium homeostasis. The recent renewed interest in vitamin D results from a worsening trend of worldwide deficiency as well as novel insights regarding its effects on glucose metabolism, endothelial function, and the cardiovascular system [1, 2].

Most of Ukrainian population are vitamin D–deficient [3], which is cyclically aggravated in seasons with low physical activity, such as winter and spring. Obesity, including higher body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, total fat mass, and percentage of fat mass, is also a major risk factor for vitamin D deficiency [4]. In patients with hypothyroidism, the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is almost twice higher than in individuals without thyroid pathology [5].

Vitamin D levels are negatively related to insulin resistance (IR) [6] and arterial stiffness [7]. Hypothyroidism combined with vitamin D deficiency doubles the relative risk of cardiovascular disease and morta–lity compared with hypothyroidism with normal vitamin D levels [8]. IR might link vitamin D deficiency and arterial stiffness in hypothyroidism. Several interventional trials were performed to evaluate the effect of vitamin D supplementation on IR [9], endothelial function and arterial stiffness [10] in insulin–resistant subjects without hypothyroidism. One interventional study evaluated the effect of vitamin D on endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes [11]. Ho–wever, no interventional trials have evaluated the effect of vitamin D on both IR and arterial stiffness in hypothyroidism.

The purpose of the study was to investigate the effect of cholecalciferol supplementation on IR and arterial stiffness in vitamin D–deficient patients with hypothyroidism.

Materials and methods

This study was a prospective, randomized trial in patients with hypothyroidism and 25–hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) concentrations < 30 ng/ml during the screening period (from May 2016 to September 2016) in Ukraine. We enrolled participants whose thyroid–stimulating hormone (TSH) level was stable.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: ambulatory participants aged 35 to 70 years; TSH levels < 7.0 mIU/l; unchanged medication (levothyroxine, antihypertensive drugs, antilipid drugs) within 3 months before the study.

The exclusion criteria were: the use of osteoporosis medications (estrogen, selective estrogen receptor mo–dulator, bisphosphonate, vitamin D, or calcium) within 3 months before study; systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 160 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 100 mmHg; acute myocardial infarction or stroke within 6 months; abnormal liver function test (alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) ≥ 2.5–fold the upper normal limit); or alcoholism (weekly ethanol consumption ≥ 140 g).

The study was performed at the Bukovinian State Medical University in Chernivtsi. The Institutional Review Board of Bukovinian State Medical University approved the study protocol. All subjects provided written informed consent.

The recent guidelines recommend an optimal level of 25(OH)D of > 30 ng/ml [12]. Therefore, we selected 4,000 IU of vitamin D3 as the daily supplemental dose for study subjects to achieve a target level of 25(OH)D.

The participants were randomized to receive either 4,000 IU of cholecalciferol once daily (n = 30) or only levothyroxine (control group) for 12 weeks (n = 25) within 1 month of screening. A physical examination and blood chemistry were performed in all of the participants at baseline and 24 ± 4 weeks later. We also evalua–ted arterial stiffness of all patients at baseline and at the end of the study. All participants were instructed not to change their previous lifestyle, including outdoor physical acti–vity and sun exposure. We educated participants regar–ding vitamin D–rich diets. Their physicians did not change their antihypertensive, and antilipid medications, which affect arterial stiffness, during the study period.

In this study, we evaluated metabolic parameters (TSH, lipid profiles, insulin, homeostasis model assessment–IR (HOMA–IR)), C–reactive protein (CRP), brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV). We also evaluated the safety profile of vitamin D supplementation in terms of serum calcium levels, liver, and kidney function.

Patient’s body weight and height were measured with the subjects wearing light clothing without shoes. Waist circumference was measured from the narrowest point between the lower borders of the rib cage and the iliac crest. BMI was calculated as the weight (kg) divided by the height (m2). Blood pressure was measured in the sitting position after a 10–minute rest period (peripheral brachial blood pressure).

Blood samples were drawn after an overnight fast and were centrifuged immediately. Levels of serum calcium, phosphorus, creatinine, AST, ALT, lipid profiles, and TSH were measured in an overnight fasting state from 7:00 to 9:00 AM. Serum 25(OH)D was evaluated using a direct competitive chemiluminescence immunoassay. Insulin was measured by means of an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay method. The serum intact parathyroid hormone (PTH) level was determined using a chemiluminescence immunoassay (reference value 15 to 65 pg/ml).

The statistical analyses were performed using Statistica 8.0 program. The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or number (%). Data with skewed distributions are expressed as medians and interquartile ranges. Comparisons between groups were performed using two–tailed Student’s t tests. Categorical variables were compared by chi–square test. Statistical analyses were performed after logarithmic transformation in skewed distributions. A p < 0.05 was considered to indicate significance.

Results

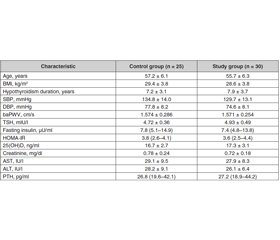

Fifty–five participants with hypothyroidism were randomized into the control (n = 25) and vitamin D groups (n = 30). There were no differences between the groups in terms of age (57.2 ± 6.1 years vs. 55.7 ± 6.3 years), hypothyroidism duration (7.2 ± 3.1 years vs. 7.9 ± 3.7 years), medications (levothyroxin, antihypertensive and antihyperlipidemic agents), smoking status. In addition, the thyroid status (TSH 4.72 ± 0.36 mIU/l vs. 4.93 ± 0.49 mIU/l), 25(OH)D levels (16.7 ± 2.7 ng/ml vs. 17.3 ± 3.1 ng/ml, p > 0.05), HOMA–IR, lipid profiles, and CRP were similar between the groups. Only one participant had PTH levels < 65 ng/mL. Baseline SBP, baPWV were similar between the groups (Table 1).

The data of 55 participants were analyzed. At the end of the study, 25(OH)D levels reached 32.7 ± 3.2 ng/ml and 18.9 ± 2.7 ng/ml in the vitamin D and control groups, respectively (p < 0.001). There were also significant differences in the adequacy of the vitamin D level (≥ 30 ng/ml). In the control group, only 8.0 % of patients (n = 2) had adequate levels of vitamin D, compared with 63.3 % (n = 19) in the vitamin D group (p< 0.001). There were no differences in changes in TSH, HOMA–IR, li–pid profiles, CRP, and PTH between groups. There were also no differences in baPWV between the control and vitamin D group.

Similarly, there were no significant changes in baPWV after adjusting for age, hypothyroidism duration, and blood pressure before and after the study. During the trial, no adverse effects related to calcium metabolism or renal and hepatic function occurred.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the effect of 12–week vitamin D supplementation in 25(OH)D–deficient patients with hypothyroidism. Vitamin D supplementation was very safe and effective in elevating 25(OH)D le–vels. 63.3 % of the participants reached the target levels of 25(OH)D in the vitamin D–treated group, compared with only 8 % in the control group during summer. Ne–vertheless, there was no beneficial effect of high–dose vitamin D supplementation on cardiovascular risk factors, including HOMA–IR, lipid profiles, CRP, SBP, baPWV, and PTH levels, in this 12–week trial.

Vitamin D deficiency is more prevalent and severe in patients with hypothyroidism compared with the normal population. Epidemiological studies revealed that vitamin D deficiency accompanied by hypothyroidism is associated with an increased risk of all–cause and cardiovascular mortality [13].

Vitamin D receptors are found in several tissue types throughout the body, including vascular smooth muscle, the endothelium, and cardiomyocytes. In many observational studies, vitamin D deficiency was strongly associated with cardiometabolic risk factors such as endothelial dysfunction [14].

IR is associated with arterial stiffness and cardiovascular diseases independent of thyroid status and hypertension. Arterial stiffness is a powerful independent marker of cardiovascular disease in patients with hypothyroidism [15]. IR might also link arterial stiffness and vitamin D deficiency in hypothyroidism. Insulin sensitivity and IR were improved significantly, and fasting insulin was decreased after daily supplementation with 4,000 IU of vitamin D in insulin–resistant Asian females compared with placebo controls.

IR was improved when the endpoint serum 25(OH)D reached ≥ 32 ng/ml [16]. However, in other trials there was no improvement in glucose metabolism, insulin secretion, or inflammatory markers despite 25(OH)D le–vels approaching 70 ng/ml [17, 18]. There was no amelioration in lipid profiles or HOMA–IR in the current study.

There were also no effects on IR (HOMA–IR), inflammatory marker (CRP), or PTH in the vitamin D group. The lack of reduction in arterial stiffness might have arisen from the negative effects of vitamin D supplementation on these arterial stiffness–related cardiovascular risk factors.

This study had several advantages over other similar works. We did not change the patients’ medications, as doing so could have affected the results. In addition, all of the participants were vitamin D–deficient. However, this study had several potential limitations. First of all, the current study included relatively few participants. As such, our study did not have sufficient power to detect small differences in metabolic parameters, HOMA–IR, or arterial stiffness between groups. It is also possible that the dose of vitamin D used was insufficient to change PTH levels significantly, which might have affected arterial stiffness.

Vitamin D supplementation in vitamin D–deficient patients with hypothyroidism might be effective and safe in elevating 25(OH)D levels. Additional long–term, high–dose, interventional trials in patients with hypothyroi–dism and vitamin D–deficiency should be performed to evaluate the effects of vitamin D supplementation on cardiovascular risk factors, such as IR and arterial stiffness.

Conclusions

1. Vitamin D levels are negatively related to insulin resistance and arterial stiffness. IR might link vitamin D deficiency and arterial stiffness in patients with hypothyroidism. However, no interventional trials on the effect of vitamin D on both IR and arterial stiffness in hypothyroidism have been performed.

2. Vitamin D supplementation had no beneficial effects on cardiovascular risk factors (lipid profiles, IR, blood pressure) or arterial stiffness (brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity) in vitamin D–deficient patients with hypothyroidism.

Conflicts of interests. Author declares no conflicts of interests that might be construed to influence the results or interpretation of their manuscript.

/669-1.jpg)