Introduction

The vaccine stimulates the immune system to produce antibodies that protect the vaccinated person from a certain disease in the future. Thus, with the immunity provided, the morbidity and mortality of infectious diseases can be reduced and controlled or eliminated In the last two centuries, vaccination programs have led to the worldwide eradication of smallpox and the disappearance of polio in most countries of the World [1]. Indeed, immunization is one of the most important achievements in the field of public health [2]. That is to say, vaccination is one of the low-cost health investments that are associated with approaches that significantly reduce childhood diseases and deaths worldwide, prevent public health discipline, protect and improve society in the long term [3]. Vaccination prevents the deaths of an estimated 6 million children under the age of 5 each year and reduces the social and economic burden of these diseases [4]. The vaccine provides both individual immunization and a reduction of the risk of infection among susceptible unvaccinated individuals by the presence and proximity of immune individuals. This is called the “herd effect” or indirect proportion [5].

Immunization services in Turkey have achieved successes such as eradication of smallpox, BCG campaigns within the scope of Tuberculosis Control, Polio Eradication, Neonatal tetanus elimination [6, 7].

Although vaccines are very reliable products, their safety and necessity can be questioned by society for various reasons. With the start of vaccination, anti-vaccination started, too [7, 8]. In the study conducted by the World Health Organization and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, the concepts of vaccine rejection and vaccine instability related to vaccination were clarified. Vaccination hesitation is a delay in accepting the vaccine or a state of refusal despite the vaccine has been reached, and it is the case for one or more vaccines. Vaccine rejection is the case of not having all vaccinations with the will to refuse [9].Today, unlike the past, anti-vaccine ideas, although they do not have a basis based on reason and science, have the opportunity to spread very quickly through the media and especially on social media [10]. In Turkey, vaccination refusals have started to occur since 2010. The most obvious example is; In 2015, when a prosecutor living in Ordu did not vaccinate his twins, the Provincial Directorate of Family, Labor, and Social Services opened a lawsuit for the health measures for their children, and anti-vaccination started to be on the agenda. According to the statement made by the Ministry of Health, the number of families who refused vaccines in our country exceeded 10,000 in 2017 and 23,000 in 2018 [11].

The reasons for vaccination opposition can be grouped under three main groups; these groups; It includes those who are concerned about the safety of vaccines, those who think they are not at risk, and those who object on religious, philosophical, or conspiracy-based grounds [12].The main objections of the groups who think vaccines are not safe enough are the concerns about the side effects caused by the vaccine and the possible long-term damage of the substances contained in the vaccines. These concerns arise from information obtained from the media or acquaintances and often have no scientific basis [13]. The frequency of side effects of the vaccine to prevent smallpox, which is eradicated today, is 1–2/1,000,000. In other words, the possibility of a vaccine for a 30 % fatal disease to cause side effects is 300,000 times less than the possibility of the disease is fatal [12].

Purpose

Vaccine opposition and instability is a complex and rapidly changing global problem that requires constant monitoring. Even small reductions in childhood immunizations due to vaccine instability can lead to greater public health and economic disadvantages when considering unvaccinated infants, adolescents, and adults [11]. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the risk perceptions and attitudes of the parents who refuse to vaccinate their children in Batman province in the Southeastern Anatolia Region, where the relative socioeconomic status and low education level is, towards a vaccine and vaccine-preventable diseases and the reasons underlying vaccine rejection.

Material and methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out between June and July 2019 in the center and districts of the province of Batman in Turkey. The population of the study consisted of 131 (0.91 %, target population at the ages of 0–5: 14,395) parents who stated vaccine refusal to their family physician in the year 2018 and their children. No sample was selected for the study, and it was aimed to reach all families who stated refusal. One hundred and five (80.2 %) parents agreed to participate in the study. The distribution of the 26 parents who were not included was related to moving to a new house (n = 13), refusing to participate in the questionnaire (n = 6), death (child) (n = 4) and not completing the questionnaire (n = 3). The data of the study were collected via face-to-face interviews by healthcare personnel knowledgeable and experienced about contagious diseases and vaccines consisting of one male and one female interviewers by visiting the homes of the participants. Before collecting the data, the researcher provided both interviewers with training on the questionnaire form. The questionnaire form consisted of 40 questions. It questioned the sociodemographic characteristics of the parents and the child, status of getting vaccinations included in the national vaccination schedule, refused vaccinations, reasons for refusal, risk perceptions, attitudes and behaviors about vaccines and vaccine-preventable diseases. Application of the questionnaire form took about 30 minutes on average. After the questionnaire form was applied, the healthcare personnel had a persuasion conversation with the families. The conversations lasted between 20 and 60 minutes. At the end of the conversations, information forms about vaccination and contagious diseases were given to the families. The parents who stated that they were convinced to get their children vaccinated were recorded in the form as persuaded. The status of getting or not getting the vaccination for the children of those who stated they were convinced was checked 4 weeks later through the electronic system. The data were analyzed by using the SPSS 25.0 software. The findings are presented as percentages, means and standard deviations. Pearson’s chi-squared test was conducted to analyze the categorical variables. In cases not satisfying the conditions of Pearson’s chi-squared test, Fisher’s Exact test was conducted. P < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

For the study to be conducted, ethical approval was obtained from the Batman State Hospital Ethics Committee with the decision numbered 134, and permission was obtained from the Batman Provincial Directorate of Health.

Results

The mean age of the parents who were interviewed in the scope of the study was 32.2 ± 6.2, and 58.1 % (n = 61) were mothers. Among the participants, 82.9 % (n = 87) lived in urban areas, while 17.1 % (n = 18) lived in rural areas. 28.6 % (n = 30) of the participants stated that they owned the house they lived in. The median number of those in the household was determined as 5 (3–18). The mean age of the mothers of the children was 30.5 ± 5.7, while the mean age of the fathers was 34.9 ± 7.6. The sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the parents are summarized in Table 1.

The decision-makers in the vaccine refusal for the children were found to be the mother and father together by 61.0 % (n = 64), the mother alone by 19.0 % (n = 20), the father alone by 17.1 % (n = 18), grandfather/grandmother by 1.9 % (n = 2) and uncle by 1.0 % (n = 1).

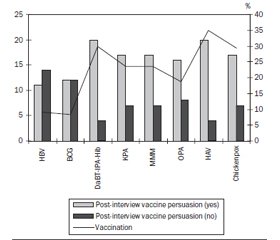

Among the children with stated vaccine refusal, 51.4 % (n = 54) were male. The mean age of the children was 23.6 ± 9.4 months. It was determined that 33.3 % (n = 35) of the children were the first child of the family. 67.6 % (n = 71) of the children had immunization cards, while 87.6 % (n = 92) had at least one dose of vaccination in the past. The vaccines received by at least one dose and those refused by the families are summarized in Fig. 1. The vaccine received by the highest rate by the families was the Hepatitis-B vaccine by 85.7 % (n = 90), while the vaccine refused by the highest rate was the DaBT-IPA-Hib vaccine by 90.5 % (n = 95).

The sources of information of the parents about health were determined respectively as healthcare personnel by 45.7 % (n = 48), social media by 19.0 % (n = 20), social environment by 15.2 % (n = 16), scientific publications by 15.2 % (n = 16) and television or newspapers by 4.8 % (n = 5).

When the parents were asked whether or not they had any of the postpartum screening tests (heel lance, hearing, congenital dysplasia of the hip, etc.) done for their children, 98.1 % (n = 103) said they had them done. The rate of the children who used modern medical treatment methods other than vaccines (antibiotic use, antipyretics, etc.) was 85.7 % (n = 90). 81.0 % (n = 85) of the parents stated that they started iron and vitamin D supplementation for their children. 43.8 % (n = 46) of the parents said they used traditional medical methods (bloodletting, leech therapy, etc.). Those who expressed their level of trust in modern medical treatment methods as none, low and medium had the rates of 3.8 % (n = 4), 6.7 % (7) and 36.2 % (n = 38), respectively.

/21.jpg)

52.4 % (n = 55) of the parents reported that they had encountered those around them who contracted vaccine-preventable diseases. They stated the health status disruption level of vaccine-preventable diseases as low, medium, high and very high by the rates of 10.5 % (n = 11), 37.1 % (n = 39), 50.5 % (n = 53) and 1.9 % (n = 2), respectively. The parents stated the probability of their child getting vaccine-preventable diseases as none by 1.9 % (n = 2), low by 25.7 % (n = 27), medium by 55.2 % (n = 58) and high by 17.1 % (n = 18). The risk status of encountering unwanted effects and formation of health problems after vaccination was perceived as very high by 6.7 % (n = 7), high by 61.9 % (n = 65), medium and lower by 31.4 % (n = 33) of the parents. Among the parents, 64.8 % (n = 68) stated that they would get the vaccine in the case of a possible epidemic caused by the microorganism on which the vaccine is effective.

When the relationship between reasons for vaccine refusal and status of post-interview persuasion was examined, it was determined that the rate of those who were persuaded was lower among the participants who thought vaccines have no benefits, those who were doubtful about the content of the vaccine, those who did not want the vaccine due to their religious beliefs and those who believed in natural immunity in comparison to the others (respectively, p = 0.003, p = 0.001, p = 0.006 and p = 0.002) (Table 2).

At the end of the interview with the parents, 22.9 % (n = 24) of them stated that they were convinced to get their children vaccinated. Following the check performed on the information of the parents who stated they were convinced, it was determined that 41.7 % (n = 10) of these parents got their children vaccinated (Figure 2).

Discussion

Factors that affect parents in their decision to refuse vaccination are complex and variable. These factors include one or multiple of highly variable reasons such as lack of information, side effects, religion and social media [11]. The sources of information of the parents in our study about vaccines were mostly healthcare workers, followed by social media and social environment. A study conducted in both Ankara and Adiyaman in Turkey reported that the information source of parents was social media by 36.3 %, whereas a study conducted in Hatay in Turkey determined that most parents obtained information from the internet [14, 15]. As media and internet publications are based on the opinions and comments of celebrities rather than scientific knowledge, any inaccurate statement leads to concerns in parents. A study carried out in Czechia revealed that, while parents who refused to get their children vaccinated mostly (55 %) collected information from the internet, those who preferred to get their children vaccinated mostly (58 %) received information from specialists [16]. Although media sources are frequently used, they are not always reliable sources, and the reliability of information obtained from physicians is higher [17].

In our study, it was determined that the vaccine the parents got their children to receive at the highest rate was the Hepatitis-B vaccine. As the first dose of the Hepatitis-B vaccine is administered at the hospital at birth according to the national immunization schedule, this may have resulted in the high rate of vaccination. Additionally, a study conducted in Zonguldak in Turkey asked mothers to list the vaccines they knew of, and it was determined that the rate of the participants to know the Hepatitis-B vaccine was high (91.1 %) [18]. A study carried out in Adana in Turkey reported that the vaccine that was administered completely at the highest rate in children whose parents stated their refusal of vaccination was the BCG vaccine (35.6 %), followed by the Hepatitis-B vaccine (18.6 %). As the BCG vaccine (single-dose in the 2nd month) and the Hepatitis-B vaccine (0th, 1st and 6th months) are administered in the first months of infants’ lives in Turkey, this may be considered as an expected result [19].

The vast majority of the parents in our study stated that they thought the risk of formation of unwanted effects and health problems after vaccination was high. Similarly, in a study in Italy, when parents were asked why they would not get their children vaccinated, their response was that they feared its side effects (91.5 %, 95% CI: 83.2–99.8) [1]. 74.7 % of parents in a study in Sweden and 44.0 % in a study in Uganda said they were concerned about the side effects of vaccination [20, 21]. Factors such as the previous experiences of families with healthcare services, family histories, control feelings and conversations with friends may affect the decision-making process about vaccination [1]. In our study, it was also found that the rate of the parents who had doubts about the content of vaccines to be persuaded to vaccinate their children at the end was lower than others (p = 0.001). Indeed, vaccination has been a topic of several myths regarding the relationship between the Hepatitis-B vaccine and multiple sclerosis or between the MMR vaccine and autism. Most studies conducted so far have not determined a relationship between the Hepatitis-B vaccine and MS development, while only a few studies stated that the possibility of MS developing should be kept in consideration. A small number of studies researching the effects of vaccination on relapse risk could not find a relationship between vaccination and attacks [22]. Fear of autism is still a frequently reported concern on vaccine safety among parents. It was claimed that there was a relationship between mercury, which used to be included in the MMR vaccine in the past, and autism, and this led to concerns in parents. In studies that were carried out, no connection was found between Thimerosal (ethylmercury) found in the vaccine and autism [23, 24]. Nevertheless, the vaccines that have been administered in Turkey and the world in the last decade do not contain mercury [25].

In our study, the parents who did not want their children to get vaccinated due to religious beliefs and those who believed in natural immunity were found to have lower rates of being persuaded in comparison to the other groups (respectively, p = 0.006, p = 0.002). As also reflected in the local media, some families in Turkey refuse to get their children vaccinated due to reasons such as “vaccines contain pig blood, vaccines are unsafe, they do not have a halal certificate”. After these objections, in the 100-day action plan of Turkey, it was stated that a “domestic vaccine” would be produced as an important step to be taken in the field of health, but the experts of the topic defend the view that there is a need for a regulation for “compulsory vaccination” [11]. Although none of the parents who refused vaccination in a study conducted in Korea stated their reason as religious beliefs, a study in Pakistan revealed that religious beliefs were among the main reasons affecting the status of vaccination. It may be a factor that needs to be investigated that parents may decide upon whether or not their children will get a vaccine based on the religious beliefs of the society of which they are members [26, 27]. As in the case in our study, some parents have misconceptions such as that “natural immunity is better, more vaccine-preventable diseases are harmless for a child, and while infections experienced through their natural course provide lifelong immunity, the immunity gained with vaccination is short-term” [28]. Two separate studies conducted in Kansas and Northern California in the United States of America determined that some parents who stated vaccine refusal thought natural immunity is better for their children than immunity gained by vaccination, and if the child gets the preventable disease, this will help the child’s immune system to be stronger in the future. Parents who think this way do not see or know about the deadly or debilitating aspects of diseases, and they also neglect the benefits gained from herd immunity [12, 13].

The study has some limitations. In this cross-sectional study, it is not possible to evaluate factor and result variables in temporal dimensions. Since the study was carried out with children who were registered with family physicians, no information could be obtained about children who were not registered with the family physicians and who were rejected by vaccination and their families. Although the province in which the study was conducted shows similarities with the surrounding provinces in socioeconomic and cultural terms, it may not represent the country.

For this reason, although the results can be generalized to the region where it is located, it is not possible to generalize to the whole country.

Conclusions

Immunization services are among the most important public health interventions in terms of preventing vaccine-preventable diseases and mortalities. As seen in our study, regarding concerns about side effects and doubts about contents which are effective in vaccine refusal, efforts should be spent to increase accurate information transfer to the public and reduce the visibility of inaccurate information by physicians with scientific evidence, by using the local and social media when necessary. Provision of family collaboration and counseling, professional conduct of society-based health education programs and implementation of vaccine advocacy by decision-makers on a legal level in addition to physicians will protect children from diseases through vaccination, which is the most basic component of the rights of children to a healthy life.

Received 04.05.2021

Revised 14.05.2021

Accepted 22.05.2021

Список литературы

1. Facciolà A., Visalli G., Orlando A. et al. Vaccine hesitancy: An overview on parents’ opinions about vaccination and possible reasons of vaccine refusal. J. Public Health Res. 2019 Mar 11. 8(1). 1436. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2019.1436.

2. Glanz J.M., Newcomer S.R., Narwaney K.J. et al. A population-based cohort study of undervaccination in 8 managed care organizations across the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2013. 167(3). 274-81. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.502.

3. Eskiocak M., Marangoz B. Status of Immunization Services in Turkey 2019. (Türkiye’ de Bağışıklama Hizmetlerinin Durumu). [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ttb.org.tr/kutuphane/turkiyede_bagisiklama.pdf. Accesed 5 February 2021.

4. United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). Research Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices in Relation to Immunization of Children In Serbia 2018. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/serbia/en/reports/knowledge-attitudes-and-practices. Accesed 5 February 2021.

5. Naafs M.A.B. Herd Immunity: A Realistic Target? Biomed. J. Sci Tech. Res. 2018. 9(2). 1-5. doi: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.09.001779.

6. Kanra G., Tezcan S., Badur S. et al. Hepatitis A seroprevalence in a random sample of the Turkish population by simultaneous EPI cluster and comparison with surveys in Turkey. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2002. 44(3). 204-10. PMID: 12405430.

7. Kanra G., Tezcan S., Badur S. et al. Hepatitis B and measles seroprevalence among Turkish children. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2005. 47(2). 105-10. PMID: 16052847.

8. Soysal A. Anti-Vaccine (Aşı Karşıtlığı). Madde, Diyalektik ve Toplum. 2018. 3. 263-71. [Internet]. Available from: http://bilimveaydinlanma.org/content/images/pdf/mdt/mdtc1s3/asi-karsitligi.pdf. Accesed 5 February 2021.

9. Larson H.J., Jarrett C., Schulz W.S. et al. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: The development of a survey tool. Vaccine. 2015. 33(34). 4165-75. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.037.

10. Badur S. Anti-Vaccine Groups and Unfair Accusations Against Vaccines. ANKEM Journal. 2011. 25(Ek 2). 82-6. Available from: https://www.ankemdernegi.org.tr/ANKEMJOURNALPDF/ANKEM_25_Ek2_82_86.pdf.

11. Sarp Üner, Kezban Çelik ST. Çocuk Aşılarında Artan Kararsızlık: Nedenleri Farklı Aktörlerin Deneyiminden Anlamak. Ankara: Hipokrat Press. 2020. 30-122.

12. Aker A.A.Vaccine Refusal. Community And Physician. 2018. 33(3). 175-86.

13. McKee C., Bohannon K. Exploring the reasons behind parental refusal of vaccines. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018. 21(2). 104-9. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-21.2.104.

14. Topçu S., Almış H., Başkan S. et al. Evaluation of Childhood Vaccine Refusal and Hesitancy Intentions in Turkey: Correspondence. Indian J. Pediatr. 2019. 86(3). 38-43. doi: 10.1007/s12098-018-2772-3.

15. Çıklar S., Güner P.D. Knowledge,Behavior and Attitude of Mother’s about Childhood Immunization and Reasons of Vaccination Rejection and Hesitancy: A Study of Mixt Methodology. Ankara Med. J. 2020. 20(1). 180-95. doi: 10.5505/amj.2020.80148.

16. Dáňová J., Šálek J., Kocourková A., Čelko A.M. Factors Associated With Parental Refusal Of Routine Vaccination in The Czech Republic. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health. 2015. 23(4). 321-3. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a4395.

17. Cataldi J.R., Dempsey A.F., Leary S.T.O. Measles , the media , and MMR : Impact of the 2014 — 15 measles outbreak. Vaccine. 2016. 34(50). 6375-80. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.048.

18. Kürtüncü M., Alkan I., Bahadır Ö. The Knowledge Levels Of Mothers About The Vaccination Status Of Children Living In A Rural Area Of Zonguldak. Electronic J. Vocat Coll. 2017. 7(1). 8-17. Available form: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/390420.

19. Hasar M., Özer Z.Y. Reasons for vaccine rejection and opinions on vaccines. Cukurova Medical Journal. 2021. 46(1). 166-76. doi: 10.17826/cumj.790733.

20. Byström E., Lindstrand A., Bergström J. et al.Confidence in the National Immunization Program among parents in Sweden 2016 — A cross-sectional survey. Vaccine. 2020. 38. 3909-17. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.01.078.

21. Vonasek B.J., Bajunirwe F., Jacobson L.E. et al. Do Maternal Knowledge and Attitudes towards Childhood Immunizations in Rural Uganda Correlate with Complete Childhood Vaccination? PLoS One. 2016. 11(2). 1-16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150131.

22. Seleker F. Multipl Skleroz Tanı ve Tedavi Kılavuzu. İstanbul: Galenos Press, 2016. 75-78. Available from: https://www.noroloji.org.tr/TNDData/Uploads/files/tnd-ms-k %C5 %BElavuzu.pdf.

23. Miller M.D., MSPH L., Reynolds R.N. et al. Autism and Vaccination-The Current Evidence. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2009. 14(3). 166-72. 25. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2009.00194.x.

24. Offit P.A. Thimerosal and Vaccines — A Cautionary Tale. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007. 357(13). 1278-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078187.

25. Gür E. Vaccine hesitancy — vaccine refusal. Turkish Archives of Pediatrics. 2019. 54(1). 1-2. doi: 10.14744/TurkPediatriArs.2019.79990.

26. Fawad S., Shah A., Ginossar T. et al. This is a Pakhtun disease:Pakhtun health journalists' perceptions of the barriers and facilitators to polio vaccine acceptance among the high-risk Pakhtun community in Pakistan. Vaccine. 2019. 37(28). 3694-703. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.05.029.

27. Chang K., Lee S.Y. Why do some Korean parents hesitate to vaccinate their. Epidemiol. Health. 2019. 41. 1-10. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2019031.

28. Smith T.C. Vaccine Rejection and Hesitancy : A Review and Call to Action. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017. 4(3). 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofx146.

/19.jpg)

/21.jpg)

/19_2.jpg)

/20.jpg)