Журнал "Гастроэнтерология" Том 55, №3, 2021

Вернуться к номеру

Поширеність синдрому надлишкового бактеріального росту серед пацієнтів із хронічними запальними захворюваннями кишечника, його вплив на показники нутритивного статусу та клінічні прояви

Авторы: Yu.M. Stepanov, M.V. Titova, N.V. Nedzvetska

SI “Institute of Gastroenterology of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine”, Dnipro, Ukraine

Рубрики: Гастроэнтерология

Разделы: Клинические исследования

Версия для печати

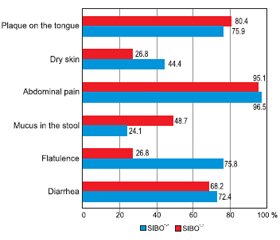

Актуальність. Останніми роками спостерігається висока зацікавленість щодо поширеності синдрому надлишкового бактеріального росту (СНБР) у тонкому кишечнику в різних популяціях. Відомо, що хронічні запальні захворювання кишечника (ХЗЗК) є гетерогенною групою розладів із високим ступенем географічної мінливості щодо симптомів, характеру прогресування, клінічних проявів або зі сполученням з іншими типами патологій. Зважаючи на те що участь мікробіому кишечника відіграє важливу роль в етіопатогенезі запальних захворювань кишечника, поєднання СНБР та ХЗЗК все частіше розглядається та досліджується останнім часом. Оскільки симптоматика обох патологічних станів значно перекликається, а отже і посилюється при поєднанні, прояви мальнутриції стають більш вираженими, що негативно впливає на нутритивний статус пацієнтів із ХЗЗК. Мета дослідження: визначити частоту СНБР в осіб із ХЗЗК залежно від нозологічних форм та дослідити його влив на клініко-лабораторні показники нутритивного статусу та клінічні прояви. Матеріали та методи. Було обстежено 100 пацієнтів із ХЗЗК віком від 19 до 79 років (у середньому (42,54 ± 1,50) року), у тому числі 70 осіб із неспецифічним виразковим колітом (НВК), 30 — із хворобою Крона (ХК). Усім хворим були проведені загальноклінічне обстеження, антропометричні вимірювання, загальний та біохімічний аналізи крові (із визначенням загального білка, альбуміну, преальбуміну). Для характеристики стану мікробіоти тонкого кишечника (наявності СНБР) усім хворим проведений водневий дихальний тест із навантаженням глюкозою з використанням газоаналізатора Gastro+ Gastrolyzer компанії Bedfont Scientific Ltd (Великобританія). Результати. Аналіз частоти виявлення СНБР показав, що зміни у стані мікрофлори тонкої кишки спостерігались у 45 % пацієнтів із ХЗЗК. Поширеність СНБР виявилася вищою в групі пацієнтів із ХК — 53,3 % (16), ніж у групі з НВК — 41,4 % (29). Наявність СНБР у групі хворих на НВК мала статистичну значущість та прямий кореляційний зв’язок із тривалістю захворювання — (9,3 ± 6,2) проти (2,9 ± 3,1) року (р = 0,001, r = 0,55). Спостерігалося зниження ваги та індексу маси тіла в пацієнтів із СНБР, особливо в осіб із ХК: так, середній показник індексу маси тіла в цих хворих становив (19,8 ± 3,5) кг/м2. Виявлено вірогідну різницю між рівнями загального білка у хворих із СНБР та без нього як у загальній групі, так і в групі НВК: (65,8 ± 8,4) проти (70,2 ± 8,2) г/л (р = 0,009, r = –0,232) та (66,5 ± 8,3) проти (70,7 ± 7,4) г/л (р = 0,029) відповідно, а також були знижені рівні альбуміну в обох нозологічних групах. Не виявлено залежності між вираженістю абдомінального болю та наявністю СНБР. При виявленому СНБР прояви метеоризму значно переважали у хворих на НВК — 75,8 % (n = 22), а діарейний синдром у пацієнтів із ХК — 75 % (n = 12). Висновки. Отримані результати свідчать про високу поширеність СНБР у пацієнтів із ХЗЗК. Пацієнти з ХК страждали від СНБР частіше (53,3 %), ніж пацієнти з НВК (41,4 %) (із переважанням хворих із тяжким ступенем вираженості). Виявлено прямий кореляційний зв’язок СНБР із тривалістю захворювання в осіб із НВК (r = 0,55; р < 0,05), що пояснюється порушенням фізіологічних бар’єрів, які попереджають виникнення СНБР, внаслідок більшої кількості епізодів загострення, тривалого прийому медичних препаратів та приєднання супутньої патології з часом. Негативний вплив СНБР на нутритивний статус проявлявся в зниженні маси тіла, індексу маси тіла та інших антропометричних (окружність середньої частини плеча, окружність м’язів плеча, товщина шкірно-жирової складки) та лабораторних (загальний білок, альбумін, преальбумін) параметрів у цих пацієнтів. Найчастішими симптомами в пацієнтів із ХЗЗК із СНБР були абдомінальний біль, діарейний синдром та метеоризм, що явно відображало типову клінічну картину СНБР.

Background. In recent years, there has been high interest in the prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) syndrome in various populations. Chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is known to be a heterogeneous group of disorders, with a high degree of geographical variability in terms of symptoms, nature of progression, clinical manifestations, or combination with other types of pathologies. Since the involvement of the intestinal microbiome plays an important role in the etiopathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease, the combination of SIBO and IBD is increasingly being considered and studied recently. Since the symptoms of both pathological conditions are significantly echoed, and therefore exacerbated by the combination, the manifestations of malnutrition become more pronounced, which negatively affects the nutritional status of patients with IBD. The purpose of the study is to determine the frequency of SIBO in patients with IBD depending on the nosological forms and to investigate its effect on clinical and laboratory indicators of nutritional status and clinical manifestations. Materials and methods. We examined 100 patients with IBD, aged 19 to 79 years, on average (42.54 ± 1.50) years, including 70 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), and 30 — with Crohn’s disease (CD). All patients underwent general clinical examination, anthropometric measurements, general and biochemical blood tests (with the determination of total protein, albumin, prealbumin). To characterize the state of the small intestine microbiota (presence of SIBO), all patients underwent a hydrogen breath test with glucose loading using a Gastro+ Gastrolyzer gas analyzer from Bedfont Scientific Ltd (UK). Results. The analysis of SIBO frequency showed the changes in the state of the small intestinal microflora in 45 % of patients with IBD. The prevalence of SIBO was higher in the group of patients with CD — 53.3 % (16) than in the group with UC — 41.4 % (29). The presence of SIBO in the group of patients with UC had statistical significance and a direct correlation with the duration of the disease — (9.3 ± 6.2) versus (2.9 ± 3.1) years (p = 0.001, r = 0.55). There was a decrease in weight and body mass index (BMI) in patients with SIBO, especially in patients with Crohn’s disease, and accounted for (19.8 ± 3.5) kg/m2. There was a significant difference between the levels of total protein in patients with SIBO and without it, both in the basic group and in the group of UC: (65.8 ± 8.4) vs. (70.2 ± 8.2) g/l (p = 0.009, r = –0.232) and (66.5 ± 8.3) vs. (70.7 ± 7.4) g/l (p = 0.029), respectively, and albumin levels were reduced in both nosological groups. No relationship was found between the severity of abdominal pain and the presence of SIBO. When SIBO was detected, the manifestations of flatulence significantly prevailed in patients with UC — 75.8 % (n = 22), and diarrheal syndrome in patients with CD — 75 % (n = 12). Conclusions. The obtained results indicate a high prevalence of SIBO in patients with IBD. Patients with CD suffered from SIBO more often (53.3 %) than patients with UC (41.4 %) (with a predominance of patients with severe disease). A direct correlation of SIBO with the disease duration in patients with UC (r = 0.55, р < 0.05) was revealed, which is explained by the violation of physiological barriers that prevent the emergence of SIBO, due to more episodes of exacerbation, long-term use of drugs and concomitant pathology with time. The negative impact of SIBO on nutritional status manifested in weight loss, reduced BMI and other anthropometric (mid-upper arm circumference, mid-arm muscle circumference, triceps skinfold) and laboratory (total protein, albumin, prealbumin) parameters in these patients. The most common symptoms in patients with IBD with SIBO were abdominal pain, diarrhea, and flatulence that reflected the typical clinical picture of SIBO.

нутритивний статус; неспецифічний виразковий коліт; хвороба Крона; антропометрія; синдром надлишкового бактеріального росту

nutritional status; ulcerative colitis; Crohn’s disease; anthropometry; small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome

Introduction

Materials and methods

Results and discussion

Conclusions

- Cohen-Mekelburg S., Tafesh Z. et al. Testing and Treating Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth Reduces Symptoms in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2018 Sep. 63 (9). 2439-2444. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5109-1. Epub 2018 May 14. PMID: 29761252.

- Stepanov Yu.M, Titova M.V., Stoikevich M.V. Nutrytyvnyi status khvorykh na khronichni zapalni zakhvoriuvannia kyshechnyka ta metody yoho otsinky [Nutritional status of patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease and methods for its assessment]. Gastroenterologia. 2019. 4 (53). 273-281. (in Ukrainian).

- Khan I., Ullah N., Zha L. et al. Alteration of Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Cause or Consequence? IBD Treatment Targeting the Gut Microbiome. Pathogens. 2019 Aug 13. 8 (3). 126. doi: 10.3390/pathogens8030126. PMID: 31412603; PMCID: PMC6789542.

- Lo Presti A., Zorzi F., Del Chierico F. et al. Fecal and Mucosal Microbiota Profiling in Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Microbiol. 2019 Jul 17. 10. 1655. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01655. PMID: 31379797; PMCID: PMC6650632.

- Shah A., Morrison M., Burger D. et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019 Mar. 49 (6). 624-635. doi: 10.1111/apt.15133. Epub 2019 Feb 8. PMID: 30735254.

- Greco A., Caviglia G.P., Brignolo P. et al. Glucose breath test and Crohn’s disease: Diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and evaluation of therapeutic response. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2015. 50 (11). 1376-81. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2015.1050691. Epub 2015 May 19. PMID: 25990116.

- Kulygina Yu.A., Osipenko M.F., Lukinov V.L., Lukashova L.V., Pomogaeva A.P. Sindrom izbytochnogo bakterial’nogo rosta i gastrointestinal’nye simptomy u pacientov s vospalitel’nymi zabolevanijami kishechnika [The bacterial overgrowth syndrome in the small intestine and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases depending on the presence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome]. Experimental and Clinical Gastroenterology. 2018. 159 (11). 68-74. doi: 10.31146/1682-8658-ecg-159-11-68-74. (in Russian).

- Adike A., DiBaise J.K. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Nutritional Implications, Diagnosis, and Management. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2018 Mar. 47 (1). 193-208. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2017.09.008. Epub 2017 Dec 7. PMID: 29413012.

- Andrei M., Gologan S., Stoicescu A., Ionescu M., Nicolaie T., Diculescu M. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth Syndrome Prevalence in Romanian Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr. Health Sci. J. 2016 Apr-Jun. 42 (2). 151-156. doi: 10.12865/CHSJ.42.02.06. Epub 2016 Jun 28. PMID: 30568826; PMCID: PMC6256157.

- Danilova N.A., Abdulhakov R.A., Abdulhakov S.R., Odincova A.H., Ramazanova A.H., Sadykova L.R. Sindrom izbytochnogo bacterial’nogo rosta u pacientov s vospalitel’nymi zabolevanijami kishechnika [Syndrome of intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases]. Prakticheskaja medicina. 2015. 6 (91). 122-126. (in Russian).

- Ponziani F.R., Gerardi V., Gasbarrini A. Diagnosis and treatment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016. 10 (2). 215-27. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2016.1110017. Epub 2015 Dec 4. PMID: 26636484.

- Massey B.T., Wald A. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth Syndrome: A Guide for the Appropriate Use of Breath Testing. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021 Feb. 66 (2). 338-347. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06623-6. Epub 2020 Oct 10. PMID: 33037967.

- Losurdo G., Leandro G., Ierardi E. et al. Breath Tests for the Non-invasive Diagnosis of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2020 Jan 30. 26 (1). 16-28. doi: 10.5056/jnm19113. PMID: 31743632; PMCID: PMC6955189.

- Rezaie A., Pimentel M., Rao S.S. How to Test and Treat Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: an Evidence-Based Approach. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2016 Feb. 18 (2). 8. doi: 10.1007/s11894-015-0482-9. PMID: 26780631.

/20.jpg)

/21.jpg)

/22.jpg)