Резюме

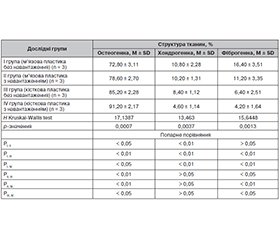

Актуальність. Незважаючи на давність операцій з ампутації, до цього часу недостатньо висвітлені питання ремоделювання кісткової тканини кукси і фактори, що на них впливають. Мета: дослідити особливості ремоделювання кукси кістки та можливості його оптимізації в умовах герметичного закриття кістковомозкової порожнини та механічного навантаження. Матеріали та методи. Проведено чотири серії дослідів на 36 кроликах з ампутацією стегна в середній третині. У І серії під опилом кістки зшивали м’язи-антагоністи. У ІІ, крім міопластики, проводили механічне циклічне навантаження кукси ударною хвилею з енергією 0,5 мДж/мм2, частотою 2 Гц з подачею 400 імпульсів за сеанс. У ІІІ серії опил герметично закривали губчастим трансплантатом. У ІV серії, крім закриття опилу трансплантатом, проводили механічне циклічне навантаження кукси аналогічно з другою серією через 4, 8, 16 тижнів після ампутації. Терміни спостереження — 6, 10, 18 тижнів. Метод дослідження гістологічний. Результати. У І серії в значній кількості дослідів відмічалось патологічне ремоделювання кісткової тканини з розвитком атрофії, порушення форми кінця кукси, її викривлення, стресові переломи, остеопороз. У ІІ серії результати були аналогічними. У ІІІ серії в найближчі терміни (6 тижнів) ремоделювання відбувалося як фізіологічне, а у віддалені (18 тижнів) — розвивались поширені дегенеративно-дистрофічні процеси. У ІV серії в усі терміни спостерігалось ремоделювання, наближене до фізіологічного. Висновки. Початок механічного навантаження через 4 тижні після міопластичної ампутації викликає поглиблення дегенеративно-дистрофічних і некротичних процесів та призводить до патологічного ремоделювання кісткової тканини, розвитку остеопорозу та стресових переломів. За відсутності механічного навантаження герметичне закриття кістковомозкової порожнини дозволяє отримати органотипову циліндричну форму кукси вже в термін 6 тижнів після ампутації, що можна розцінити як фізіологічне ремоделювання. У віддалені терміни (10–18 тижнів після ампутації) відсутність механічного навантаження призводить до порушень ремоделювання з розвитком остеопорозу. Герметичне закриття кістковомозкової порожнини з механічним навантаженням кукси дозволяє отримати її органотипову форму з повною завершеністю ремоделювання.

Background. Despite the long history of amputation surgery, issues related to the remodelling of bone tissue in stumps and the factors influencing them remain insufficiently studied. Aim: to investigate the features of bone stump remodelling and the possibilities for its optimisation in conditions of hermetic closure of the medullary cavity and mechanical loading. Materials and methods. Four series of experiments were conducted on 36 rabbits with amputation of the thigh in the middle third. In the first series, antagonist muscles were sutured under the bone end. In the second series, in addition to myoplasty, mechanical cyclic loading of the stump was performed with a shock wave with an energy of 0.5 mJ/mm2, a frequency of 2 Hz, and 400 pulses per session. In the third series, the bone end was hermetically sealed with a cancellous graft. In the fourth series, in addition to closing the bone end with a graft, mechanical cyclic loading of the stump was performed similarly to the second series 4, 8, and 16 weeks after amputation. The observation periods were 6, 10, and 18 weeks. Histological studies were performed. Results. In the first series, a significant number of experiments showed pathological remodelling of bone tissue with the development of atrophy, distortion of the stump end, its curvature, stress fractures, and osteoporosis. In the second series, the results were similar. In series III, remodelling occurred as physiological one in the short term (6 weeks), while widespread degenerative-dystrophic processes developed in the long term (18 weeks). In series IV, remodelling close to physiological one was observed at all time points. Conclusions. The start of mechanical loading 4 weeks after myoplastic amputation causes deepening of degenerative-dystrophic and necrotic processes and leads to pathological remodelling of bone tissue, the development of osteoporosis and stress fractures. In the absence of mechanical loading, hermetic closure of the medullary cavity allows for the formation of an organotypic cylindrical shape of the stump within 6 weeks after amputation, which can be regarded as physiological remodelling. In the long term (10–18 weeks after amputation), the absence of mechanical loading leads to remodelling disorders with the development of osteoporosis. Hermetic closure of the medullary cavity with mechanical loading on the stump allows its organotypic shape to be obtained with complete remodelling.

Список литературы

1. Renstrom PAFH, Alaranta H, Pohjolainen T. Review: leg strengthening of the lower limb amputee. Critical Reviews™ in Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 1995;7(1):11-32. DOI: 10.1615/CritRevPhysRehabilMed.v7.i1.20.

2. van Velzen JM, van Bennekom CA, Polomski W, et al. Physical capacity and walking ability after lower limb amputation: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20(11):999-1016. doi: 10.1177/0269215506070700.

3. Ma Q, Miri Z, Haugen HJ, et al. Significance of mechanical loading in bone fracture healing, bone regeneration, and vascularization. J Tissue Eng. 2023 22;14:20417314231172573. doi: 10.1177/20417314231172573.

4. Bonucci E, Ballanti P. Osteoporosis-bone remodeling and animal models. Toxicol Pathol. 2014;42(6):957-69. doi: 10.1177/0192623313512428.

5. Datta HK, Ng WF, Walker JA, et al. The cell biology of bone metabolism. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61(5):577-87. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.048868.

6. Robling AG, Castillo AB, Turner CH. Biomechanical and molecular regulation of bone remodeling. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2006;8:455-498. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095721.

7. Shevchuk V, Bezsmertnyi Y, Jiang Y, et al. Vascularization of a bone stump. Med Glas (Zenica). 2024 Feb 1;21(1):214-221. doi: 10.17392/1677-23. https://orcid.org//0000-0003-1105-4795.

8. Shevchuk VI, Bezsmertnyi YO, Vezsmertna HV, Dovga–lyuk TV, Jiang Y. Changes in the structural organization of bone after amputation. Polish Annals of Medicine. 2020;27(2):147-53. /doi.org/10.29089/2020.20.00121.

9. Shevchuk VI, Bezsmertnyi YO, Bezsmertna HV, et al. Reparative regeneration at the end of bone filing after ostoplastic amputation. Wiad Lek. 2021;74(3 cz 1):413-417. DOI: 10.36740/WLek202103106.

10. Yazicioglu K, Tugcu I, Yilmaz B, et al. Osteoporosis: A factor on residual limb pain in traumatic trans-tibial amputations. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2008;32(2):172-8. doi: 10.1080/03093640802016316.

11. Bemben DA, Sherk VD, Ertl WJJ, Bemben MG. Acute bone changes after lower limb amputation resulting from traumatic injury. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(7):2177-2186. doi: 10.1007/s00198-017-4018-z.

12. Mauntel TC, Marshall SW, Hackney AC, et al. Trunk and Lower Extremity Movement Patterns, Stress Fracture Risk Factors, and Biomarkers of Bone Turnover in Military Trainees. J Athl Train. 2020;1;55(7):724-732. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-134-19.

13. Flint JH, Wade AM, Stocker DJ, et al. Bone mineral density loss after combat-related lower extremity amputation. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(4):238-44. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182a66a8a.

14. Sherk VD, Bemben MG, Bemben DA. BMD and bone geometry in transtibial and transfemoral amputees. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(9):1449-57. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080402.

15. Frost HM. Wolff's Law and bone’s structu–ral adaptations to mechanical usage: an overview for clinicians. Angle Orthod. 1994;64(3):175-88. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1994)064<0175:WLABSA>2.0.CO;2.

16. Gailey R, Allen K, Castles J, et al. Review of secondary physical conditions associated with lower-limb amputation and long-term prosthesis use. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45(1):15-29. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2006.11.0147.

17. Rubin CT, Lanyon LE. Regulation of bone formation by applied dynamic loads. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(3):397-402. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6699056/.

18. Shevchuk V, Bezsmertnyi Y, Branitsky O, et al. Remo–deling of the Fibula Stump After Transtibial Amputation. Orthop Res Rev. 2024;16:153-162. doi.org/10.2147/ORR.S459927.

19. Shevchuk V, Bezsmertnyi Y, Jiang Y, et al. Influence of post-amputation pain syndrome on blood circulation in the bone residual limb. Pain, Joints, Spine. 2023;13(2):85-92. doi.org/10.22141/pjs.13.2.2023.370.

20. Bezsmertnyi YO, Bondarenko DV, Shevchuk VI, Bez–smertna HV. Bilateral Stress Fractures of Amputated Tibial Stumps in the Setting of Chronic Compartment Syndrome. Orthop Res Rev. 2024;16:273-281. doi: 10.2147/ORR.S485472.

21. Lopalco G, Cito A, Iannone F, Diekhoff T, et al. Beyond inflammation: the molecular basis of bone remodeling in axial spondyloarthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Front Immunol. 2025 Jul 31;16:1599995. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1599995.

22. Low EE, Inkellis E, Morshed S. Complications and revision amputation following trauma-related lower limb loss. Injury. 2017;48:364-370. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2016.11.019.

23. Tirrell AR, Kim KG, Rashid W, et al. Patient-reported Outcome Measures following Traumatic Lower Extremity Amputation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9(11):e3920. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003920.

24. Matsuzaki H, Wohl GR, Novack DV, et al. Dama–ging fatigue loading stimulates increases in periosteal vascularity at sites of bone formation in the rat ulna. Calcif Tissue Int 2007;80(6):391-399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-007-9031-3.

25. Parfitt AM. Bone remodeling. Henry Ford Hosp Med J 1988;36(3):143-144. https://scholarlycommons.henryford.com/hfhmedjournal/vol36/iss3/4.

26. Leelarungrayub D, Saidee K, Pothongsunun P, et al. Six weeks of aerobic dance exercise improves blood oxidative stress status and increases interleukin-2 in previously sedentary wo–men. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2011;15(3):355-362. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2010.03.006.

27. Santos RV, Viana VA, Boscolo RA, et al. Moderate exercise training modulates cytokine profile and sleep in elderly people. Cytokine. 2012;60(3):731-735. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.07.028.

28. Reiner B, Christoph B. Modelling and remodelling of bone. In: Bone disorders. Cham: Springer, 2017, pp. 21-30, 1st ed. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-29182-6_3.

29. Hwang MP, Subbiah R, Kim IG, et al. Approximating bone ECM: crosslinking directs individual and coupled osteoblast/osteoclast behavior. Biomaterials. 2016;103:22-32. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.06.052.

30. Knothe Tate ML. “Whither flows the fluid in bone?” Аn osteocyte’s perspective. J Biomech. 2003;36(10):1409-1424. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00123-4.

31. Osteocyte necrosis triggers osteoclast-mediated bone loss through macrophage-inducible C-type lectin. PubMed. Avai–lable online at (Accessed December 13, 2024).

32. Bratengeier C, Liszka A, Hoffman J, Bakker AD, Fahlgren A. High shear stress amplitude in combination with prolonged stimulus duration determine induction of osteoclast formation by hematopoietic progenitor cells. FASEB J. 2020;34:3755-72. doi: 10.1096/fj.201901458R.

33. Yu L, Ma X, Sun J, et al. Fluid shear stress induces osteoblast differentiation and arrests the cell cycle at the G0 phase via the ERK1/2 pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:8699-708. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7720.

34. Turner CH. Site-specific skeletal effects of exercise: importance of interstitial fluid pressure. Bone. 1999;24(3):161-162. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00184-7.

35. Kuchan MJ, Frangos JA. Shear-stress regulates endothelin-1 release via protein-kinase-C and cGMP in cultured endothelial-cells. Am J Physiol. 1993;264(1 Pt 2):150-156. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.1.H150.

36. Takuwa Y, Masaki T, Yamashita K. The effects of the endothelin family peptides on cultured osteoblastic cells from rat calvariae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;170(3):998-1005. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90491-5.

37. Zaidi M, Alam AS, Bax BE, et al. Role of the endothelial cell in osteoclast control: new perspectives. Bone. 1993;14(2):97-102. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(93)90234-2.

38. Glatt V, Evans CH, Tetsworth K. A concert between bio–logy and biomechanics: the influence of the mechanical environment on bone healing. Front Physiol. 2017;7:678. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2016.00678.